Red Poems Speak the Truth Behind Breast Cancer’s Pink

- Sep 26, 2018

- 4 min read

Red Poems Speak the Truth Behind Breast Cancer’s Pink

by Amy Alexander

We are approaching October, the pink month.

Pink for breast cancer survivors.

It’s a particularly poignant time for me, because I lost my own mother to breast cancer on July 6, 2015. My relationship with breast cancer goes back longer, though, to the time when my mother was first diagnosed, in 2002. She lived with the disease for 13 years until it spread to her abdomen in 2014.

Since she got her diagnosis, I’ve had annual mammograms, nervous palpation with every moon, and the regular finding of suspicious lumps that need to be biopsied.

Every October, when the pink appears in in grocery stores, malls, stadiums, and other random spots, I often wonder: What is the point of all this pink? It doesn’t make me feel better.

I know, I know, it’s to remind the general public, those whose days are quickly ruffled through like pages in a boring magazine, that there is this disease that lives inside of women’s breasts that we need to do something about, or at least feel gratitude for the health we have.

Those who are living with it are marked as unique. In pink.

My own mother grew to despise the color pink. She was gifted regularly with necklaces bearing pink diamelles, pink little statues, safety pins festooned with beads in baby colors, tee shirts, nightgowns, shoes in shell shades.

Her cancer journey went so much deeper, past pink, and well into the deep red of passion, blood, marrow, rubies.

On August 10, the poet Anya Silver died after living for 14 years with inflammatory breast cancer.

She was brought to my awareness by the editorial team at the outstanding Memoir Mixtapes, when they published, in vol. 4, April 2018, this luminous piece by Silver in which she describes what it is like to live with metastatic breast cancer.

She rattles off the anthems that breast cancer survivors get lobbed at them, everything from “Fight Song,” by Rachel Patton to “Live Like You Were Dying,” by Tim McGraw.

Her song is different: Lana Del Rey’s “Ride.”

Cancer, she says, makes you feel lonely but also, in some strange way, free and unpredictable.

Cancer makes you a wild rebel.

I think my mother would have applauded that take. In her last year, I saw, in her, a fierceness that she had not displayed to anyone before. When she decided to stop the chemotherapy, she became a rambler, roving to Hawaii and into the deep south, untethered by tubing and riding her life all the way to the end, with a pocketful of pain pills.

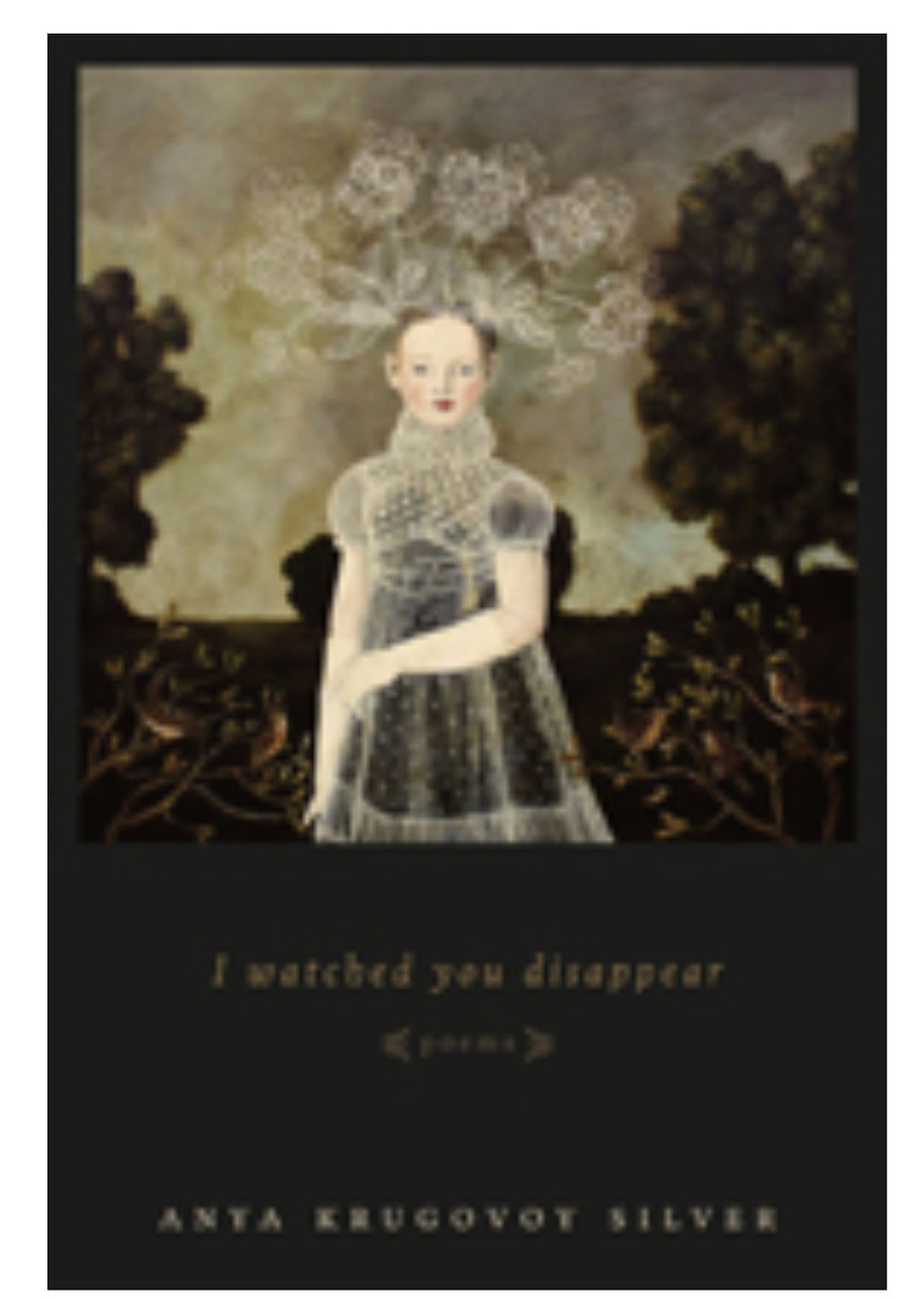

Lately, I have been spending some time with Silver’s collection, “I Watched You Disappear.”

My favorite section in the book is the second one, which contains mostly sonnet-type poems, with fourteen lines.

The final poem in the section, The Hazel Tree, is eleven lines long, though, and seems to be a message to her son. It was during her pregnancy with him that Silver discovered she had breast cancer. After giving birth, she had a mastectomy and hoped she would live long enough for him to know her. Those deep in love never live long enough to see that love into extinction. It only grows. The eleven lines seems a statement from Silver that the poem she writes to her son will never be finished.

“The mother died and grew into a tree,” she writes:

Each nut a word she’d grown to tell her son

now that her speaking human voice was gone;

that she’d chanted stories into his blood,

sown language in his eyes so he could dream.

(From I Watched You Disappear, © 2014 LSU Press)

When my mom was dying, even after hospice was brought in, she was so stubborn and refused to admit it was the end. She wouldn’t talk to me about dying, maybe because she couldn’t bear to.

During one of our last conversations, Mom told me that she was very sad seeing all of the clothes in her closet that she wouldn’t get to wear. The clothes became a metaphor for all of the time we did not have together anymore. The missed celebrations and quiet chats over coffee. That little, specific detail of her life carried so much richness and meaning, mother to daughter.

It makes me realize, in hindsight: Poetry is what we need at times like this, not pink. Anya Silver knew that. So did Mom.

Poetry is best for expressing the complex, individual path traveled by every woman who has faced a breast cancer diagnosis and is living, day by day, after that transformative moment.

I propose poems on cans, poems on tee shirts, poems pinned in place, poems painted on buses and streaking past on football jerseys.

Red poems to speak the truth behind the pink.

Annual

by Amy Alexander

To dance with the image maker

takes special skill.

I put on garments for it.

We are never alone,

guided, always,

by a knowing woman

who drapes my arm

across and over metal parts

I name after different words

for cold.

I tilt my brow,

touch my forehead

to all the wives and daughters who have gone before me.

Inhale

Unspoken prayers

exhale

Mother

inhale

gone now

exhale

give me one more year.

Amy Alexander is a writer and artist from Baton Rouge whose work has appeared most recently in Anti-Heroin Chic, Cease, Cows, The Mojave Heart Review, and Dirty Paws Review. She'll have a poem in Issue Three of Rhythm & Bones Lit. Her chapbook, "The Legend of the Kettle Daughter," is forthcoming in April of 2019 from Hedgehog Poetry Press. Follow her on Twitter @iriemom.

Comments